Over the years, I have acquired some YouTube skills. I assume that the pandemic has had something to do with it, and while I’m not really a YouTuber and my channel isn’t popular by any means, I think I can say that I have some YouTube skills—at least more than many other academics do.

Many of us find ourselves in the position where we need to maintain a YouTube channel or create some video content, whether that’s recordings of talks or teaching materials. And for that context, I do think I’ve actually learned quite a bit, and I’ve wanted to share some of my best advice with you. This is not about how to edit a video—I think you can probably find better content out there on the internet that stays up to date—but there are a few things that I have learned about using YouTube as an academic (more like context) that may be relevant for you.

I’ll be talking a lot about two different video schools in this video, so here are the relevant links:

- My YouTube channel

- Video School: Digitizing the Materiality of the Premodern Book (Playlist)

- Video School: Computer Vision for Digital Humanists (Playlist)

How I ended up on YouTube in the first place: Pandemic teaching videos

So, what did I learn about doing YouTube as an academic? First of all, my YouTube channel started during the pandemic, like many others. I created some initial videos in German for a class I taught online with pre-prepared videos. The idea was to provide input sessions as videos so students could pause and re-watch them as needed. Although I haven’t taught XSLT since then, except in the Harvard XSLT workshop, I’ve heard some people still use these videos to teach themselves XSLT. However, they haven’t been particularly useful in my actual teaching lately, as I haven’t taught an XML/XSL class in a while. One video that I did use in my teaching is a gentle introduction to SQL. I provided this video for students as my class often their first encounter with programming and the video helped reduce panic and dropouts towards the end of the course (this is in the past tense because I’m currently not teaching anymore at all, unfortunately, at my new job). Since including this video, fewer students failed to submit their final projects. The video covers the basic steps needed to set up SQL, which helped students feel more confident.

That eight-minute video took about eight hours to edit back then, mainly because I wasn’t good at editing yet. This was some of my early YouTube experience.

I also uploaded some of my talks to YouTube, not expecting many viewers, but to give potential future employers a sense of who I am. This may be less relevant nowadays that I’m more well-known in the community, especially in the German DH community, but back then it made sense to me.

I came back for posting video schools as part of a project

I only really got into YouTube was when we created video schools as part of a project. Naturally, the videos were supposed to go on YouTube, and that’s when I realized I’d need to understand the platform better. I had a channel, I kind of knew how it worked—but I wasn’t what you’d call a power user. My XSLT videos did okay, probably because it’s such a niche that I was the only person posting tutorials on it. I even got a comment once like, “I can also read your slides, I don’t need someone to read them to me.” Fair. Not every video was didactically amazing, but I zoomed into what mattered, because I found early-pandemic video classes super frustrating—blurry code and tiny fonts on a huge, confusing screen. I made a point of fixing that in my own content.

Anyway, we produced two rounds of actual video schools based on in-person summer and winter schools. The first time we filmed while the event was happening (stressful!). The second time, we refined the material first, making the most out of the feedback from the in-person event, then recorded it separately. The format was 90-minute lectures, sometimes cut into segments, sometimes not. But that just doesn’t work for YouTube. People don’t sit through hour-and-a-half lectures there, and I didn’t think enough about that upfront. I assumed the quality and relevance of the content would carry it. Spoiler: it didn’t.

In hindsight, for the video classes we produced with significant grant funding, I should have paid more attention to how the YouTube algorithm works. This is really why I’m writing this blog post: so that others don’t make the same mistake.

While my XSLT videos get a constant stream of (a little bit of) traffic for some reasons that are beyond me, better understanding and optimizing for the YouTube algorithm may have significantly increased the reach and impact of our high-quality video content.

If you plan on investing time and money into videos on Youtube, learn about optimizing for its algorithm first

Professional editing and high-quality free content aren’t enough to make it on YouTube

Initially, I didn’t focus on optimizing for YouTube. I believed the content was valuable and relevant, so people would find it. However, the videos aren’t performing well, despite the high production quality and the funding that went into having them recorded and edited professionally. For some reason, back than I assumed that just having things professionally filmed would make it more interesting for potential viewers but really, my badly done pandemic teaching videos are doing better than the highly produced content. That was a bit of an eye-opener for me!

These were high-quality, grant-funded videos—well-produced, comprehensive introductions to digital scholarly editing and computer vision. Honestly, if I’d found something like this online back when I needed it, I’d have been thrilled. The content of the computer vision school is probably already going out of date at the time of writing this (at least parts of it) but the content from the other school is pretty evergreen and based on my years of experience teaching topics like digital scholarly editing.

The original goal of these video schools was to create what I didn’t have: a free, accessible resource for self-directed learning. For instance, the “Digitizing the Materiality” school was inspired by my experience at Rare Book School—where I once attended an insanely expensive online course where the digital humanities aspects weren’t even that great (in my opinion). So we thought: as a digital humanities center, we can do this better—and free. Education shouldn’t be behind a paywall in my opinion.

But people aren’t finding any of those videos because YouTube isn’t serving them to anyone. So despite all my good intentions, we’re not reaching anyone.

You need to optimize upload schedules and thumbnails

I think part of the issue is that I didn’t optimize the uploads. I posted videos quickly, without proper descriptions or thumbnails. I just chose snapshots that seemed relevant, and surprise: they tanked. I now realize thumbnails matter a lot. They’re part of how YouTube decides whether to show your content to more people. The thumbnail needs to be attention-grabbing and clickable (as this will determine your so-called “click-through-rate”). I eventually learned (the hard way) how to make good ones—bold text, clear visuals, even a “before–after” style that works well. But the algorithm had already decided my videos weren’t interesting. I’ll get more into the thumbnails later.

Also, we probably shouldn’t just have uploaded them all at once: YouTube prefers channels with a regular uploading schedule. Given that I haven’t uploaded anything new for ages now, my videos are not being shown to anybody.

Shorts and Longer Form Content Viewerships Don’t Really Mix

At some point, I tried generating traffic via Shorts but that really wasn’t worth the effort either (and, it turns out, that viewers from Shorts and viewers from videos are often a different viewership that doesn’t actually transfer. That’s why many creators have different channels for Shorts and longer form content.)

It’s hard to branch out of your niche without ruining the branding (and thus, reach) of your channel

Some YouTube channels emphasize sticking to a niche or maintaining a consistent personal brand so that viewers have something to grab onto. Posting content that doesn’t appeal to your existing audience can hurt your metrics, causing YouTube to show your videos less. In hindsight, I think part of the problem may have been that I mixed niches too much. XSLT and digital scholarly editing might overlap, but computer vision? Totally different audience. That kind of confused my channel and likely hurt my reach further. It may have split my audience, leading the metrics to tank (you need to convert people whom your content is shown to into viewers and then keep them watching as long as possible).

Learning from a video school doesn’t give you a certificate

And sure, our “Digitizing” class has a lot of the introductory content that is Rare Book School’s sales proposal. But RBS also has brand value—it looks good on a CV. Maybe it’s not so much that people actually want to learn the content but they also want the certificate that they got into a prestigious, expensive programme to learn it? Back when I wanted to learn this material, it was more important to me to learn it asap, without any gatekeeping or delays (back when I took my RBS class, I didn’t even get into the one I wanted but then had to attend something because I had received funding to attend RBS and it would only be valid for that year… stupid system if you ask me).

But now we have built a free alternative that teaches the basics really well, and people still don’t find or use it. Maybe that audience just isn’t on YouTube. Maybe they’re not even looking?

Professional creators sometimes spend up to 50% of their time optimizing thumbnails and titles to reach their audience!

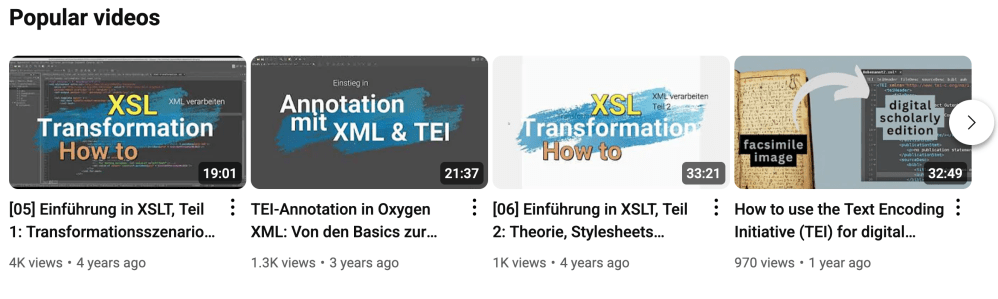

My initial lack of understanding about creating effective thumbnails probably hurt viewership. Last Easter, I spent time learning about thumbnails and now I understand their importance (but it was already too late, of course). A video that helped me explained different types of thumbnails, highlighting the effectiveness of before-and-after thumbnails or those with clear, bold text and an interesting image (such as thumbnails with a historical object, like a rare book, I reckon). You can actually see this effect with the few (still inexpertly done) thumbnails that I created for my own content. The ones with the before and after seemed to actually work much better than the other ones.

Unfortunately, I didn’t have these thumbnails when I first posted the videos, which is crucial for initial traffic. Now, the YouTube algorithm thinks my videos aren’t interesting and doesn’t show them to many people. Academic content generally doesn’t perform as well on YouTube, but I think we could have done better with proper optimization.

My personal YouTube lessons learned (the hard way)

So yeah, I guess I was a little naive initially and just laser-focused on creating great quality content, which is the most important content strategy (and I still believe in that). But that made me overlook the role the YouTube algorithm plays. Even though the content I was producing was very high quality and a valuable resource (that there must be demand for somewhere), I may have been mistaken about how interested people really were in this. However, I believe the main problem is that we’re not reaching the interested audiences. There must be people interested because the Rare Book School is always overbooked and I’ve personally struggled to get into some classes. So, there are people interested in these topics; they just don’t know or can’t find this content.

How come, despite the high attendance of Rare Book Schools, our free alternative hasn’t reached a larger audience? Maybe I should create a clickbaity blog post like, “Didn’t get into Rare Book School? Try our school instead.” Maybe I will 😉 (Edit: I did.)

Anyway, I should have focused more on understanding what the YouTube algorithm wants, the niches of my account, and not posting all the videos at once. Posting them week by week would have given me content for half a year and would have allowed traffic to build slowly. But we had the end of the project coming up and a strategy like this wasn’t planned in the original project proposal. We needed to get the project results out to show to the grant funding agency.

Back then, I did create video descriptions and used hashtags, but the hashtags didn’t help much with traffic. Even when I saw my own videos in the timeline, I wouldn’t have clicked because the thumbnails were so boring (to be perfectly honest). I think the thumbnails were probably the single most limiting factor. Now I understand how to make them, and I think the new ones I created are quite cool (given my limited skills). I’d appreciate your feedback on them and the video schools if you happen to look into them!

Unfortunately, the initial poor thumbnails seem to have hurt my ratings in the YouTube algorithm in lasting ways. Maybe we can still generate some slow-burn traffic from this blog post.

If you’re going to post videos to YouTube, take the platform seriously (or your efforts will be lost)

So what is my final verdict from this experience? What advice you I give you if you’re planning on embarking on a similar quest?

If you really want to go through with posting your content on YouTube, make sure you understand how it works first (learn about the key metrics, thumbnails, posting schedules, etc). The closer you get to how professional (successful) creators are doing it, the better chance your content will stand.

But make no mistake, you won’t get lots of views with academic content unless it’s super optimized for what YouTube viewers are currently into. Yet, understanding that and optimizing for it is a whole profession of its own (content creator) and for good reason: it’s not that trivial.

So unless you want to move into a content creator career and get actual training in it (or otherwise invest significant amounts of time in acquiring these skills), you need to live with meager view counts. And reflect on how much work you really want to put into producing those videos and the more general administrative work of “doing YouTube” given that you won’t get a massive return from it.

If you just want to post recordings of your talk series, why not. Maybe it makes sense for you to just do it with the least amount of effort. That way, the recordings are available if someone wants them but you don’t waste too much time on it.

If it’s fun to you, maybe do some market research and try things out (like I did last Easter). Just know what to expect. Just know that you likely won’t get many views at all. If you still enjoy putting in that work to make it look nice, sure, go ahead. But I personally would try to use the Pareto (80/20) principle, spend a little more time on the thumbnails and then leave the videos to their own devices, so to speak 😉

If you’re planning a project like this: take YouTube seriously. Spend time learning the basics—watch a few videos on content strategy and thumbnails during lunch. It took me two full days of trial and error to get a thumbnail style I liked, and now I can do one in 20–30 minutes. Are they truly good? I wouldn’t know. Probably not. But they’re definitely much better than what I had first put out. I wish I’d focused on the marketing part sooner.

The sad part of my own experience is, it’s not like we wasted the grant money—we created something good. That I truly believe in. But it’s not reaching the people it was supposed to help and that’s frustrating. Maybe this blog can help redirect some traffic.

(But better only click if you’re genuinely interested—because otherwise, you’re just wrecking my click-through rate 😉 )

If you’re getting into this space, I wish you better luck than I had.

And a bit of thumbnail wisdom to start with!

That’s it for today. Stay tuned, and don’t make the same mistakes I did!

Yours,

the Ninja

Buy me coffee!

If my content has helped you, donate 3€ to buy me coffee. Thanks a lot, I appreciate it!

€3.00