As most of us will probably know by now, machine learning has become a big part of digital humanities projects, especially in the computational humanities, and more and more people are trying to implement it. It’s becoming increasingly accessible, even to people who don’t have massive machine learning skills, and more and more people are getting involved in these projects. Most people have a broad idea of how machine learning works. I have this old blog post on it—although I suppose now I could write a better one; maybe I will at some point—but you will find enough introductions out there on how machine learning works.

TLDR: This post covers making your own labeled data for machine learning in Humanities contexts (more conceptually and less practically than How to create your own fine-tuning or training dataset for computer vision using Supervisely) and specifically, how much time to budget and how to go about it according to me.

There’s more to it than the ML Hello World examples

However, one thing that I feel there isn’t enough information on is how to actually go about fine-tuning something. Of course, it’s nice to be able to use a Hello World example of machine learning. There are so many of those out there on the internet—tutorials, for example, on how to use your first CNN using the MNIST dataset to classify handwritten digits (see Medium or this Github), or the Fashion MNIST (Medium, Tensorflow or Kaggle), which is kind of the same thing with clothes, only with maybe a few more classes, not sure. And then there’s also flowers with the Iris dataset (see Medium or this Github). But what all these datasets have in common is that they don’t have much in common with humanities use cases. (Maybe the digits are kinda relevant for optical character recognition, for which I also have prepared an introductory blog post that gives you the absolute basics.)

But really, what you probably want to know is: how do I apply this to humanities data? And this is where these tutorials leave a huge gap because they don’t tell you how to create your own fine-tuning data. Without that, how are you supposed to apply this to your own data? Of course it’s nice to be able to classify some random flowers but that’s not really what you want to do right? And it hardly brings you further towards your goal.

I actually tried proposing a tutorial for the Programming Historian on this topic, but somehow it didn’t get accepted. Maybe they had too many applications or they thought the last blog post I wrote on the topic was too similar to what I had proposed. But honestly, this last blog post is very long, detailed, very concrete about how to make the annotations in Supervisely—I think that’s going to help you a lot if you want to learn how to use that specific tool.

However, I realize that there are many other questions about this. I have written the aforementioned blog post and wrote a data paper on the dataset, the process, and the results of this annotation process that is described in the aforementioned blog post. I’ve gotten feedback from machine learning people saying “Wow, this is so great. Humanities data is generally very interesting for machine learning because they sometimes lack really interesting problems of their own” basically. (Of course, they do have some problems of their own, but humanities has really many interesting problems for machine learning people and it’s often hard to find good datasets. So share your datasets!)

Anyways… From the humanities side, the most frequent question that I got was: how long does this take? People want to put it in their grant proposal, and they want to know how much time to budget. So I thought, okay, I’m here for you. Here you go. I’ll explain everything in this blogpost and, as you know me, I had some more thoughts 😉

I had actually already said this in the last post, but because the last post is very technical and things can get lost in there, I thought I’d put it here again and talk some more about it. So, back to basics:

Why do we even need these annotations in the first place? Fine-tuning algorithms

First of all, you need those annotations to fine-tune or train an algorithm so that it knows your historical domain. Many of these algorithms will work surprisingly well from scratch on data that transfers pretty well to the modern training data it was trained on. For example, many studies where computational humanities people used computer vision algorithms successfully used relatively recent data. For comparison, I work with 17th-century material, and they sometimes worked with 19th-century material like photographs or magic lantern slides—so much later.

The types of data that were closer to modern-day photographs worked pretty well almost from scratch. However, in my experience, I’m noticing this is not the case at all with more “historical” objects, specifically those that are not in use anymore. For example, the objects typical of alchemy don’t really have any correspondence in modern photos that would be part of big photo datasets that modern algorithms are trained on.

The humans, plants, and animals in my alchemical data get recognized really well. Also, different models vary quite a bit in what they struggle with, so if you try one out and it fails, don’t give up yet. Try some other ones, because our experiments have shown that they can perform quite differently, and sometimes the classes with which they struggle are not the same ones. So definitely try out different models.

Anyway, the things that the algorithms most struggled with were the specific alchemical objects. Often, the issue has to do with granularity, at least in my cases. Let me explain: For example, an algorithm would classify the whole page of my early modern book as a book page—which technically is correct. But of course, I already know this is a book page; what I want is a different granularity. I want it to look specifically at a specific type of object within a scientific illustration. Detecting a scientific illustration at all is something that has been working pretty well, but looking at these specific objects—the algorithm just can’t really distinguish what’s an object I’m interested in and what’s another one that I don’t care about, because the training hasn’t been in the right granularity.

This is where fine-tuning comes in and hopefully helps you get better results.

You need ground truth information in a suitable data format

To be able to form said fine-tuning, you will need data in a specific format that is usable for an algorithm. Usually, in the case of computer vision applications, this will be some sort of “location”—telling the algorithm which data points are we interested in—and then a label for what the thing in question should be classified as.

(Of course, there are so many different types of machine learning algorithms and some of them differ quite drastically in what they do, given that they’re all kind of similar technologies. But you do have to know specifically what your task is and then what datasets they expect and how the algorithms work. You can find this information; it’s readily available online. Also note that we created this video school Computer Vision for Digital Humanists that will teach you all you need to know.)

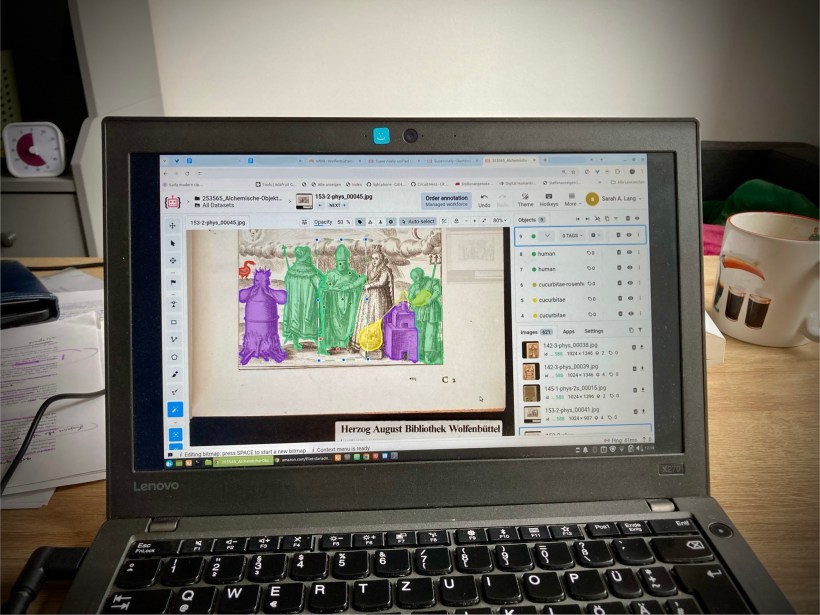

For example, in my computer vision task, what I usually need is a bounding box—so, drawing a box around my object—and then I also have pixel-level annotations, meaning basically drawing the line around the shape that I’m interested in (which you can read about in this other blog post). This gives me the relevant pixels, and then I also get a label associated with these pixels so that the machine can know what class I want this labeled as.

You need an interface to create these annotations with

So, to get started, I first of all need some sort of interface to create this information for the algorithm in a way so that it can understand what I want. One of them, for example, is Supervisely, which you can use paid, but you can also just log in with GitHub and use the service for free and get a certain number of daily annotation points. I was able to finish my project without paying for it, so I liked it. Plus, it has lots of export options that are really helpful.

For example, I’ve also discussed some data formats, such as MS COCO or YOLO in the last post, because, for example, the YOLO algorithm has a specific format that it wants its training data to come in to be able to actually use it. So, having a platform that can give you different annotation formats, like Supervisely in this case, is quite helpful. (I’m giving them free advertisement, but they’ve also given me their product for free, basically, so I think that’s fair. I’ve had good experiences with the tool, but I’m not getting paid by them or anything, of course.)

Anyway, you need to know how this process works and then you need to know what interface you can use.

I also know that many projects that have a machine learning practitioner working together with humanities people have the machine learning person program a simple interface to let a Humanities person do the annotations.

For example, there’s a Python package, ipyannotations, that I’ve been recently introduced to, where you can make the annotations directly in a Jupyter notebook. There’s FRAT, developed by a former colleague in Graz. I know that my new colleagues at Max Planck in Berlin have their own annotation interfaces. So all these things exist, but if you don’t have access to a machine learning person of your own, you can always use Supervisely, for example.

How long does it take? What to say in your grant proposal

Now that we’ve gone through this general introduction on how the annotations work, why you need them, etc., let’s get to one question that I was asked the most and this is: how long does it take? What do I write in my grant proposal? Who is supposed to do this work? The quick answer is 40-60 hours for my data set. But you might want some more context, which is what I’ll give you here.

Many people think “Okay, this sounds like student assistant work” and for my dataset, what I did is around 40 to 60 hours. However, what you need to know about my dataset is that this is the second iteration. In the first attempt, we worked with around 30 pages and really few annotations for a few-shot approach. It didn’t work that well, but I think it was a good attempt at the time—or it was good thinking—because few-shot approaches are so effective. We thought, if we can just show a few examples, maybe the algorithm will already know what to do. This was not the case for our specific experiment. But because we wrote that up as an article and had came up with an annotation scheme back then, I already had quite some experience. I already knew, for example, with which annotation decisions I’d made back then were useful and which were not that great.

So for my second attempt—which the data paper is about (and the blog post as well)— I already knew the objects, I knew the results from my last experiments, I knew where the pain points were, I knew where we had to do some adaptations to how I annotated. Because in the first attempt, I had made some decisions a bit differently: Technically, YOLO (You Only Look Once algorithm) expects you to have one annotation per page—like one class per page, no overlapping annotations—and I realized that my data just doesn’t look like that. Initially, for that reason—for the requirements of YOLO—we had annotated the data quite differently. I had excluded composite objects that would always contain overlapping elements and tried to decompose them into their parts. We had worked using bounding boxes to cut out the relevant parts of a page to make sure there’s only one annotation per page.

But in my second attempt, I decided that I was not going to do that anymore, because that’s simply not what my data looked like. And I’m never going to get a satisfactory result if we work with data that’s butchered so much that it doesn’t actually correspond to how the historical data work. I thought we need to get the algorithm to understand the data as it is somehow. And so I annotated all the objects I found.

If I were to do a third round—or a round of edits, in fact—from my experiences from annotating these first two rounds, I would do things differently. Definitely. I’m writing a little bit about that in the data paper if you’re interested in the process. And maybe if you want to cite that in your grant proposal, then this is maybe the more elegant thing to cite than this blog post. But feel free to cite this blog post too. (There’s one of my old blog posts, the one about computational humanities and toxic masculinity, that I feel is getting cited more than my actual articles in the scholarly literature. Anyway, tangent. Let’s get back to it.)

So if I were to do it again, I would do it differently. And I think at some point in the future, I’m going to make some changes. For example, in the second round of annotations, I realized that the furnace class should have been subdivided into different types of furnaces, because they look quite distinct from one another. I realized—unlike what I initially thought—that there would have been easily enough examples for each of the furnaces. So the furnaces should have been subdivided. Whereas I used the original classification from Ute Frietsch—that I’m writing about in the data paper and also explaining in the initial publication we wrote about this—that distinguished bottle-like flasks and other flasks. In some cases, this is quite clear and the distinction makes sense. But in many other cases, visually, there really isn’t much of a difference. So I would now introduce a superclass to cover both of them and then subdivide in the class on the level below. Because visually, that just makes so much more sense.

What I’m trying to say here is: Annotation is challenging, complicated and iterative. You need someone who understands the data and who will dare contradict if things don’t make sense.

How much expertise do you need to do this task?

And another thing: I’ve been working in alchemy for many years. The annotation was sometimes difficult, even for me. I had to make hard decisions regularly.

I’m not a chemist and not a material culture expert, so these different types of laboratory objects are a challenge—I knew them, of course, from being in the alchemy sphere for a few years—but I was not an expert. There now is a big book about these objects (that I have also written a book review about but no I can only find this other review by somebody else). It’s a great book. But when I first started this project, this book wasn’t there. I had to figure it out for myself. This was a lot of work. And even when this book was available to me, the annotation process is not that trivial.

Many people think this is a task that you can give to a student assistant. Depending on what the task is, honestly, I would disagree. I think in my concrete example—I mean, I don’t want to overshoot—but I think this is a task for a postdoc. This was extremely difficult. Even for me, it was challenging. Of course, at some point after 500 of these objects, you get the hang of things. But still, even then, I sometimes had to go back into the text, see what’s written about the objects in Latin, and then research basically what the best annotation decision would be.

This, of course, wasn’t the case in all of these examples, but it had a very steep learning curve, even for me, who has been working on alchemy since 2017. So basically, at the time of doing this, I had been familiar with alchemy research for at least six years. And even then, it was still a challenging task.

I think maybe if the annotation task is something that is directly part of the research subject of a PhD student or the PhD student has worked on it for maybe a year already, or maybe done a master’s thesis about the topic already and you’re sure that the person is really confident making these annotations, then maybe you could give it to a PhD student. But I think this concrete task would have been impossible to annotate for a student assistant. Or if they wanted to do it well, it would have taken much longer than it took me. And it did take me 40 to 60 hours at least (not calculating the time it took to set up the project, publish it on Github or as a data paper).

So don’t underestimate this.

I also feel that in the digital humanities, we know that annotation is a challenging, hermeneutic task and it has a lot to do with hands-on work with the data. But I recently gave a talk to traditional historians of science and they were surprised how much of just traditional working with historical data was part of this annotation process. They would have thought that computational humanists don’t do that—but we do.

Anyway. Maybe there are some examples that are really easy to annotate for a student assistant. But don’t underestimate this task. I also felt like for me—especially in this specific task—to do it well, or maybe even to do it half well (because I think a lot of what I did there is not perfect. I’m sure there are some mistakes in there that need fixing in the future. I’m sure some annotation decisions could have been done differently. And I think the more experience I still gain on the project, the more I would do some things differently), there’s so much reflection—like self-reflection, data criticism, self-criticism—involved in this process. I’m not sure if someone who is really new to research would be able to do this work. Not because I don’t like student assistants or anything, but because I think I, at an earlier stage of my career, would have not been able to do this task well. And even now I doubt how well I actually completed this task.

Then again, I think with someone too senior, you also have to be careful, because it has to be someone who’s kind of affiliated with digital humanities or who can be convinced to not go crazy with the annotation categories. Because algorithms do want a limited number of categories and someone who’s very senior, has been working 20+ years in this field etc, they are sometimes hard to convince that you need to keep the number of classes down—and that you sometimes need to batch two classes up into one, even though that’s not technically 100% correct.

So I think, honestly, someone at my career level would be kind of ideal for the task. I also know that something similar has been done in the Graz ERC project on medieval charters, where a postdoc was doing this work.

Conclusion

Don’t underestimate how challenging and how skilled a task annotation can be, how much reflection is needed—because after all, you don’t want just any annotations. If you put in this work—and it is substantial work—then you want the result to be good. You want it to be correct. Otherwise, you might as well not do it at all, or do the whole shebang (research) by hand instead of training an algorithm. The data that the algorithm learns from determines what it does. It really needs to be good.

So don’t underestimate the skills required for this task.

That’s it from me today. I hope this was helpful!

So long and thanks for all the fish!

Buy me coffee!

If my content has helped you, donate 3€ to buy me coffee. Thanks a lot, I appreciate it!

€3.00