Everybody is talking about “materiality” but what does that even mean? It’s actually kind of hard to understand the materiality of books and texts if you have never had training working with physical books. On the other hand, if you know how to work with books, you may not be familiar with Digital Humanities skills enough to create a digital scholarly edition. You may be wondering what the heck XML is supposed to mean (hint: I got you covered) or, if you have worked with TEI before, you may realize at some point after completing your TEI-encoded edition that that’s not all there is by any means. There are so many more skills involved!

That’s why we created a self-learning video class teaching foundational skills at the intersection of digitization, bibliography, and the Digital Humanities. They are crucial for many scholars, yet instruction frequently only covers one or maybe two of these intersecting aspects. For example, use of the Text Encoding Initiative XML standard is increasingly the norm in digital scholarly editing, but many individuals working with textual materials do not have access to relevant scholarly training in DH. Conversely, many DH departments, lack rare book specialists. Congratulations, you just walked into my sales pitch 😉

I have great news: My two video school projects are finally completed (this and Computer Vision for Digital Humanists) and the materials are accessible for free online: The YouTube playlist “Digitizing the Materiality of the Premodern Book” is complemented by a repository of slides. However, I think in this particular case, you don’t need the slides as much as in the Computer Vision school where you really should follow along in the Juypter Notebooks to make to most out of your learning. This playlist can be consumed at your leisure, no need to take notes 😉 Unless you want to.

So anyway, the goal of this workshop was to create one succinct class where students will learn the necessary skills for understanding how the materiality of pre-modern books can be digitized and provide a foundation for putting those skills into practice. After attending this workshop, you will (hopefully) understand the fundamentals of digitization and how books and manuscripts are described in the TEI, including the msDescription and transcription modules.

Why Do We Need to Digitize Materiality?

Digitizing the materiality, isn’t that an oxymoron, an inherent contradiction? Kind of, and it also kind of isn’t. Actually, digitizing materiality, or focusing on materiality in digital editions, has been a big topic recently and this focus has been around for a few years now. Initially, of course, with digitization taking off, people have focused on just the text of books, and then at some point, people were also digitizing objects and so on, because it’s been criticized that the Digital Humanities are too text-focused. That probably had something to do with that just being the easiest, best-funded thing with mass digitization. This is echoed in the distant viewing computer vision movement, which advocates for multimodal approaches encompassing different types of humanities data. You can also look at our computer vision school materials and the recent blog post about it, if you want to know more.

The Evolution of Digitization

The initial focus on text probably owes itself to the convenience and funding available for the mass digitization of texts. However, the field is gradually expanding to include more than just text, and this is particularly interesting in the realm of historical books (at least to me). For instance, initiatives like VD16, VD17 or VD18 collect unique copies of texts and interlink them, facilitating the comparison of variations across different libraries.

The Materiality of Historical Books

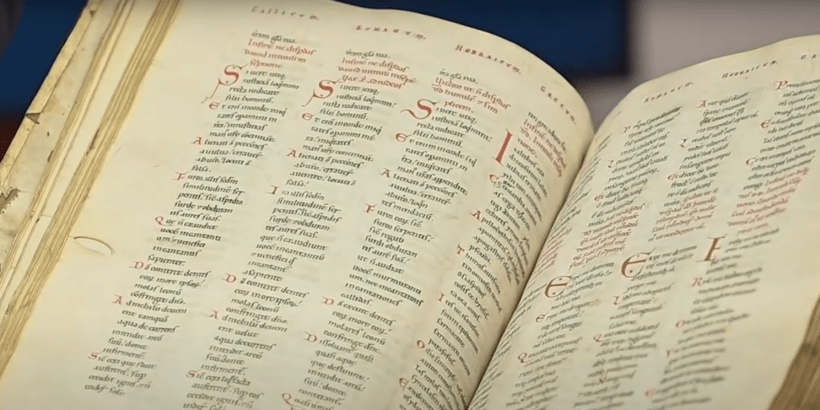

Understanding the material aspects of historical books is crucial. Unlike modern books, copies from the same print run of historical books, especially from the hand-press period, are unique due to the hand-press printing techniques used. Hence, a shift towards digitizing the material aspects of these books is necessary and already underway in some quarters.

Historical books are not like modern books in that we expect that a copy from one print run is the same as any other. In fact, because of the hand-press printing at the time, books from the hand-press period are not at all the same. Each book is a unique copy. This is why there are digitization initiatives like VD16 or VD17. These initiatives collect unique copies of a text and link them together. So if you look for one author’s text, then you can find different versions of that book in different libraries. This is actually a really exciting area of study, but it is very much rooted in book history and library science, so you may not yet have come across it. If you’re working with rare books, you will probably have come across the fact that there are different copies of different books. When I first did, I honestly never really cared too much. I just wanted to get at where is my digitized version that I can run through Transkribus and get the full transcript. But now I realize there’s so much more to a book that I never before cared to pay attention to.

Transkribus side note

Side note TLDR: On a side note, Transkribus, a widely-used text recognition software for historical documents (see Training my own Handwritten Text Recognition (HTR) model on Transkribus Lite), is apparently moving to a subscription-only model in the near future. While I understand the need for a stable revenue stream, this may push me to explore other options for future projects.

I mean, I love Transkribus, as I’ve mentioned many times, but I was inquiring about a future project and they said that they will not be offering these on-demand credits anymore, but rather a system where you have to subscribe, which honestly, I get it. They need stable revenue, but a subscription-only model makes it so much less attractive.

Honestly, I’m currently wondering if I need to start using something else? Because I guess I am somewhat of an expert user. The models that I’m using are in the public domain. I’m not using all the software around it, because lots of it caters to Humanities people who don’t necessarily want to have anything to do with the technology, maybe, or not that much. I don’t really need all that interface. I just want a tool for reliable OCR for historical texts.

Transkribus getting more and more user-friendly, and I like that. And of course, they do need to sustain themselves somehow. But honestly, not offering on-demand credits anymore at all? I don’t use Transkribus every month, so I really don’t need a subscription that charges me as if I were to use it constantly. I just use it sporadically when I have the time. So this actually prompted me to start thinking about a different solution. Let’s face it, deep learning and everything is taking off more and more than it already has. And maybe at some point soon, there will be a viable alternative. If Transkribus gets too expensive, I will have to switch.

I feel that over the last few years, everybody has moved to these subscription models, like Grammarly for example, which makes those tools not an option for me. When they have monthly subscriptions and I don’t fully make use of the complete spectrum of tools I’m paying for, then I’m unsubscribing. And finding a different alternative because there are many competitors. I mean, yeah, it’s nice to have nice grammar checking, but I didn’t like the Grammarly premium version at all. And it was really expensive. And I just have so many subscriptions now, I need to start radically cutting or else all my money is going to go into that.

Anyway, sorry for the digression and rant but this makes me kind of sad. With all the free Transkribus publicity that I have done over the past years, I would have never thought that there might come a point where I would stop using it. Especially as the tool has become really great. But ultimately, it’s not the fancy interface that I need, so somebody else can pay for that, I guess.

Conclusion and stay tuned!

That was it for today. I actually wanted to do everything in one post but, as always, it got unreasonably long. So I split it up into two posts. That means more regular posting schedule for you, no extra work for me. Maybe I need to get better at these hacks 😉

Anyway, the next post contains all the info on what you’ll actually learn in the class and how it relates to other teaching materials of mine that you may wish to link it with to create your own DH self-study curriculum 😉

So long and thanks for all the fish.

Buy me coffee!

If my content has helped you, donate 3€ to buy me coffee. Thanks a lot, I appreciate it!

€3.00

4 thoughts on “What do we mean by ‘materiality’ in the context of rare book digitization?”